Fair trade is a social movement that aims to improve the trading conditions in developing countries thanks to the payment of higher prices to the producers and a general attention to ethical, social, and environmental issues.

According to The Salvation Army, one of the earliest examples of fair trade goods ever distributed were the Hamodava beverages (tea, coffee, and hot chocolate), an initiative set up by British Herbert Booth in New Zealand in 1897.

Booth was the local Salvation Army’s commander and he saw the opportunity to import tea of the highest quality from Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) and sell it in Auckland. The peculiarities of this entrepreneurial endeavour were that all profits went directly into Salvation Army work and — above all — that the business model allowed farmers to buy back their own farms.

As the Salvation Army’s blogpost highlights, at a time when slavery was still legal in 20 countries, this was no mean feat.

The evolving business models, the 1929 economic crisis, and World War II put these early attempts at fair trade on hold. After the war, a few religious organizations tried to create fair supply chains but it was only in the 1960s that the current fair trade model was put in place in Europe with programmes such as “Helping-by-Selling” by the British NGO Oxfam.

At the time, fair trade products (mainly handcraft items and agricultural goods) were sold in so-called “Worldshops” — retail outlets often run on a volunteer basis. These outlets were often hugely successful but they certainly couldn’t compete with the massive distribution of fast-spreading supermarkets.

For this reason, in 1988, Nico Roozen, Frans van der Hoff, and Dutch ecumenical development agency Solidaridad launched Max Havelaar, the first fair trade label ever created. The organization certified that the products were produced and traded according to certain fair trade standards. This way, it became possible to distribute fair trade goods across mainstream retail stores and supermarkets as well.

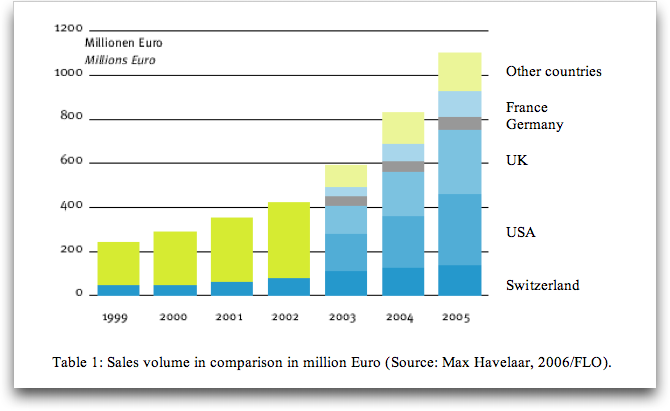

The initiative was a big success and the model was quickly adopted everywhere in Europe and also in America and Japan. Obviously, it didn't make sense to have dozens of national fair trade labels; therefore, in a few years, a process of convergence started.

The process culminated in 1997 with the creation of Faitrade Labelling Organization International or simply Fairtrade International.

It's certain that this model proved to be a brilliant solution. Over the years, Fairtrade sales increased enormously and in 2014 $6.9 billion was spent on Fairtrade-certified products worldwide.

However, sales volume was not the only thing that increased over time. Year after year, the number of criticisms raised against fair trade (or, more specifically, the Fairtrade label) surged as well.

One of the main studies that questioned this model was Fair trade and free entry: Can a disequilibrium market serve as a development tool?, published in 2015 by the MIT Review of Economics and Statistics. There, the authors analyzed data from an association of Fairtrade coffee cooperatives in Central America concluding that the producers' benefits were close to zero.

As recently as August 2017, in an op-ed for The Guardian, Senegalese economist Ndongo Samba Sylla reached the same conclusion highlighting how the Fairtrade label is really profitable only for supermarket chains.

In his book Doing Good Better: How Effective Altruism Can Help You Make a Difference, Scottish philosopher William MacAskill summarizes the three main reasons why Fairtrade doesn't work or at least is an inefficient approach to improve trading conditions in developing countries:

- When you buy fair-trade, you usually aren’t giving money to the poorest people in the world. Fairtrade standards are difficult to meet, which means that those in the poorest countries typically can’t afford to get Fairtrade certification.

- Of the additional money that is spent on fair trade, only a very small portion ends up in the hands of the farmers who earn that money.

- Even the small fraction that ultimately reaches the producers does not necessarily translate into higher wages. It guarantees a higher price for goods from Fairtrade-certified organizations, but that higher price doesn’t guarantee a higher price for the farmers who work for those organizations.

And these are just a few examples; for a complete overview of Fairtrade criticism, you can have a look here.

Then, perhaps all the problems started when fair trade became Fairtrade?

This may well be the case. And it may also be the case that a few corrections could fix this system and bring Fairtrade back to its original good intentions.

However, in Doing Good Better, MacAskill argues that there might be a much easier and more effective solution: ditch Fairtrade, buy cheaper goods at the discount store, and donate the money saved to cost-effective charities that work for improving the livelihoods of farmers in developing countries.

Fair trade has a truly honorable history but maybe it's time we started considering alternative, more efficient models.