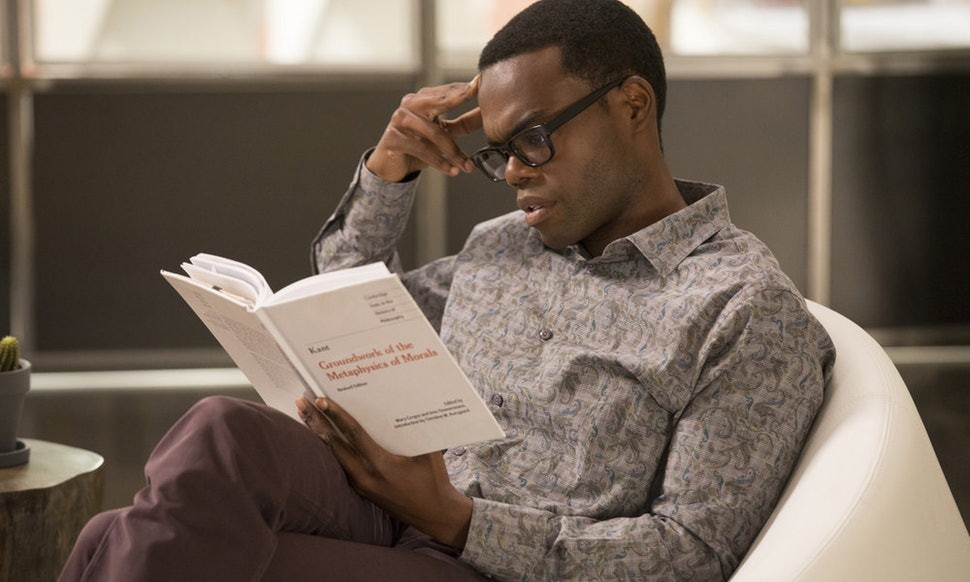

One of the main characters of the TV series The Good Place is Chidi Anagonye, a brilliant yet perennially indecisive moral philosopher. Chidi is full of good intentions but – as the saying goes – that’s what the road to hell is paved with.

Chidi’s extensive knowledge of ethical matters forces him to overthink everything, making him incapable of making decisions. As a result, despite his constant efforts to help others, Chidi doesn’t cause them anything but suffering and pain.

But, what if we could find a way to leverage our knowledge of all the world’s problems effectively? After all, we’ve never had so much information about the challenges we’re facing and how we could solve them.

That’s what the Effective Altruism movement is all about. Starting in the late 2000s by organizations like Giving What We Can and Givewell, Effective Altruism is a philosophy and social movement using evidence and reason to determine the most effective ways to do good and make the world a better place.

Think of a super-decisive Chidi that always knows what to do and you have a good example of a typical EA activist. (Aside from the fact that EA is a white-dominated movement; more on this later.)

What problems we should tackle first

One of EA’s most intriguing – and to a certain extent, most controversial – aspects is that it doesn’t just tell you what you should do if you want to solve a certain problem. It also tells you which problems you ought to solve first in order to leave this world a little bit better than you found it. For example, banning straws is not that important.

There’s a whole area of research focusing on cause prioritization and even an EA-inspired institute at the University of Oxford dedicated to it.

In a nutshell, EA suggests that good causes that should be prioritized usually have three characteristics:

- They’re great in scale: They affect many people’s lives, by a great amount

- They’re highly neglected: Few people are working to address the problem

- They’re highly solvable: Additional resources might even solve the problem once and for all

Factoring in these aspects, EA activists usually come to the conclusion that the three most-pressing issues for humanity are: extreme poverty, animal suffering, and what they call “long-term future.” That’s basically the minimization of global catastrophic risks, also known as existential risks (yes, like reaching singularity).

How we can solve these problems

When it comes to helping others, the creed is usually that there’s no better way of getting involved than dedicating our own professional lives to it. After all, who’s more altruistic than a doctor that gives up a six-figure salary to run a charitable hospital in a low-income country?

However, EA refuses – or, at least, complicates – this scenario. In his book Doing Good Better (that is sort of EA’s gospel), British philosopher William MacAskill (one of the most prominent EA evangelists), claims that certain doctors (of course, it all depends on how good these hypothetical doctors are, what their specialization is, and who would fulfill their roles if they weren’t doing what they’re doing) might do a greater good if – instead of working for a charitable organization – they’d worked for a Western hospital donating 10 percent of their fat salaries to highly effective organizations.

MacAskill calls this “earning to give” and a few years ago it was one of the most prominent EA’s fads. “Earning to give” does sound like an opportunistic way of doing good and it’s not surprising that the concept has been particularly well-received by techies. After all, what’s more appealing for a startup founder than hearing that the way they can do the most good is by pursuing their own personal interests?

At the same time, there’s robust evidence that earning to give can truly be an extraordinarily effective way of doing good.

Anyway, as I said, EA complicates, rather than refuses the idea that dedicating your own career to a good cause is the best way to save the world. There are cases in which becoming a doctor in a low-income country is the most effective way of doing good.

To help grad students, starters, and all professionals in general in their career choices, there’s an EA organization called 80,000 hours whose name refers to the rough amount of hours a person spends working over a lifetime. In this age of bullshit occupations in which the expression “meaningful job” is often reduced to a LinkedIn buzzword, an organization like 80,000 hours provides much-welcomed resources to help people lead high-impact careers.

For example, scientific research is a potentially high-impact career choice. As a tissue engineer, you could grow clean meat. As a machine learning specialist you could work to minimize the chances of global catastrophic risks, and as an economist you could research how to maximize the positive impact of charitable cash transfers. And this just to mention research that would tackle the three cause areas we should prioritize according to EA.

Altruism for the Patrick Batemans of the world

In Doing Good Better, MacAskill proposes an ethical test to his readers. Imagine you’re outside a burning house and you’re told that inside one room is a child and inside another is a painting by Picasso. You can save only one of them. Which one would you choose to do the most good?

Of course, only American Psycho’s Patrick Bateman would choose to save the painting. Yet, MacAskill argues that, if you save the Picasso, you could sell it, and use the money to buy anti-malaria nets in Africa, this way saving many more lives than the one kid in the burning house.

The argument makes sense, albeit it sounds less like a serious moral proposition than as something a know-it-all could jokingly quip. And that’s probably how MacAskill intended it.

Anyway, the child-in-the-burning-house story is a good example of the most and less convincing aspects of Effective Altruism – at least as far as I’m concerned.

Among the least convincing, there’s surely this implicit tendency of being a movement that predominantly caters to white male nerds with a major in computer science. In a memorable account for Vox, journalist Dylan Matthews recounted his experience of the 2015 EA Global conference held at Google’s Quad Campus in Mountain view. Matthews – an effective altruist himself – described the movement as “at the moment, very white, very male, and dominated by tech industry workers.” Sure, many EA groups are working to make the movement less homogeneous, but it takes time.

On the other hand, the positive moral of the Picasso vs. kid story is that if we want to do good, we need to focus on the concrete, long-term outcomes of our actions and not solely on our warm, emotional intentions. Otherwise we become like Chidi, well-meaning but ineffective, paving our way to “The Bad Place,” as hell is unsurprisingly called in the series The Good Place.

This article was originally published on Forbes