151 million — mostly young— women use it everyday, and it makes an annual revenue of 7.35 billion dollars. Ten guesses what I’m talking about? As you may have guessed from the title, it’s the pill: the worlds’ most widely used contraceptive. If you’re a woman, it’s likely there's a packet of them in your bag.

1960 marked the beginning of a new era of sexual autonomy for women. For the first time women of different ages and backgrounds could control their sex life on their own terms — or almost, as we will see. Because this new sexual autonomy came with a number of side effects; and a dark history. How did we get here?

The dark origin story of the pill

In 1957 the first oral contraceptive was launched in the US. It was called Enovid (Enavid later on in the UK) and promised to change women’s lives once and for all. Being able to limit the size of their families — thus freeing up women’s time for things other than child-rearing — marked an exciting new stage in female autonomy. The pill, at the time, had a particularly powerful impact in underdeveloped countries. Using it reduced poverty, improved overall education for both women and other members of her household, and generally granted better lives to millions of people.

But the first contraceptive pill came at a great cost. American state laws strictly regulated clinical trials related to birth control. So when Harvard graduate biologist Doctor Gregory Pinctus (a.k.a ‘the father of the pill’), had to figure out the correct dosage of estrogen and progesterone, he chose to test it on women whose lives he valued little enough to serve his purpose.

He found them in Puerto Rico, the central American Island closely linked to the US politically. In the 1950s, Puerto Rico was becoming highly overpopulated. Sterilisation was endorsed also by the United States as a solution to the problem. About a third of Puerto Rican women did, in the end, get sterilised — often after being coerced to do so. So when Pinctus’ reversible contraception was presented as an alternative, local women were more than willing to take it.

In fact, they often took it without knowing they were part of an experiment. They hadn’t been told that the drug was still in production and that they were the first women in its ‘clinical trials’, nor did they get any information about possible side effects.

When women mentioned side effects; such as nausea, depression, and blood clots, they were discarded as “unreliable”. As the undisclosed experiment went on, three women taking the pill died. Their deaths were never officially investigated, and so to this day, we are left wondering whether the pill may have been the culprit.

Only many years later, were these women told they had been guinea pigs in an experimental drug trial. Turns out, the pill they were given contained ten times the level of hormones needed (about 100 to 175 µg of estrogen and 10 mg of progesterone, while the current dosages are respectively 30 to 50 µg and 0.3 to 1 mg). Over the years, many of these women have faced severe side effects linked to the hormonal overdose; including permanent infertility, cancer, blood clots, and strokes. But the hormones they were given were effective in preventing pregnancies. So the study was considered to be a "success".

You’d think it couldn't get any worse than this. But it did! A second round of testing was carried out on women in mental institutions. Without consent or proper information, male scientists continued to exploit vulnerable patients with unethical methodologies. Eugenics was the guiding principle behind the testing — it makes one shiver to think that so recently, human beings were still being experimented on for this purpose.

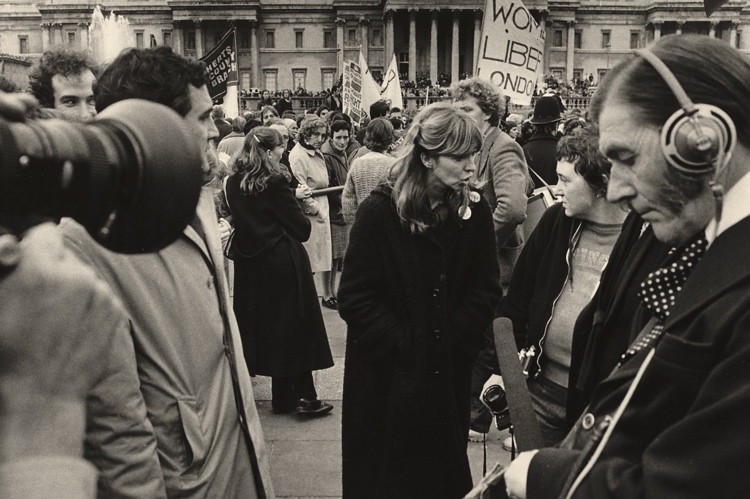

Only in 1970 was the American Congress was forced to hold a hearing on the pill’s side effects thanks to the work of feminist activists, including Barbara Seaman, a famous journalist and symbol of the fight for women’s health rights. Outrageously enough, only men were invited to the hearing. And so women, inviting themselves, showed up on the day of the hearing. It’s in part thanks to the case these women made that day, that the discussion on hormone levels in the pill brought us to where we are today.

Blood Clots

Although hormone levels in oral contraceptives have been lowered over the years, women using them still face a number of side effects. Almost everybody who has been on the pill knows this; having lived through nausea, moodswings, water retention, and spotting. But that’s not all. Blood clots are, for a small percentage of users, still a risk related to contraception based on estrogen (both oral and local). According to FSRH Clinical Guidelines, the absolute risk of blood clots is estimated to be between 5 - 12 per 10,000 users annually (compared to 2 per 10.000 in non-users.) This doesn’t take women with previous experience or family history of blood clots into account — for them, the risk is much higher.

Since millions of women around the world are exposed to these risks, it’s somewhat surprising to witness uproar about blood clot risks related to the AstraZeneca and Johnson vaccines. In fact, although the types of blood clots caused by the pill and the vaccine are different from one another, the risk is much smaller with the vaccines than it is for mixed hormonal contraception users. It is in fact estimated that Astrazeneca’s recipients have a 1 in every 250,000 chance of getting blood clots, whereas the numbers are much smaller for pill users: 1 in every 1,000 women. So why then aren’t we as shocked by the pill-related blood clots risks?

That female drugs — and products in general — are less and improperly tested is not news. This discrepancy ranges from airbag testing on male-like mannequins to adjusting the universal office temperatures to the body temperature of male colleagues. Yet, although women constitute more than half of the world’s population, there is little incentive to innovate birth control. Because producers know that women cannot go without it. As long as there are no alternatives — male birth-control options, for example — women will have to keep buying current contraceptives, even when they are faulty, and don't respond to women’s needs.

How you can help

We need proper and ethical testing of new products to turn the situation around. It seems that women are once again in the position where they need to push for change themselves. One glance at the news will confirm this. But women’s rights should matter to everyone. That’s where you can help: by getting informed on the topic, talking about it to people around you, and supporting Kinder’s United Action for Women’s Rights.