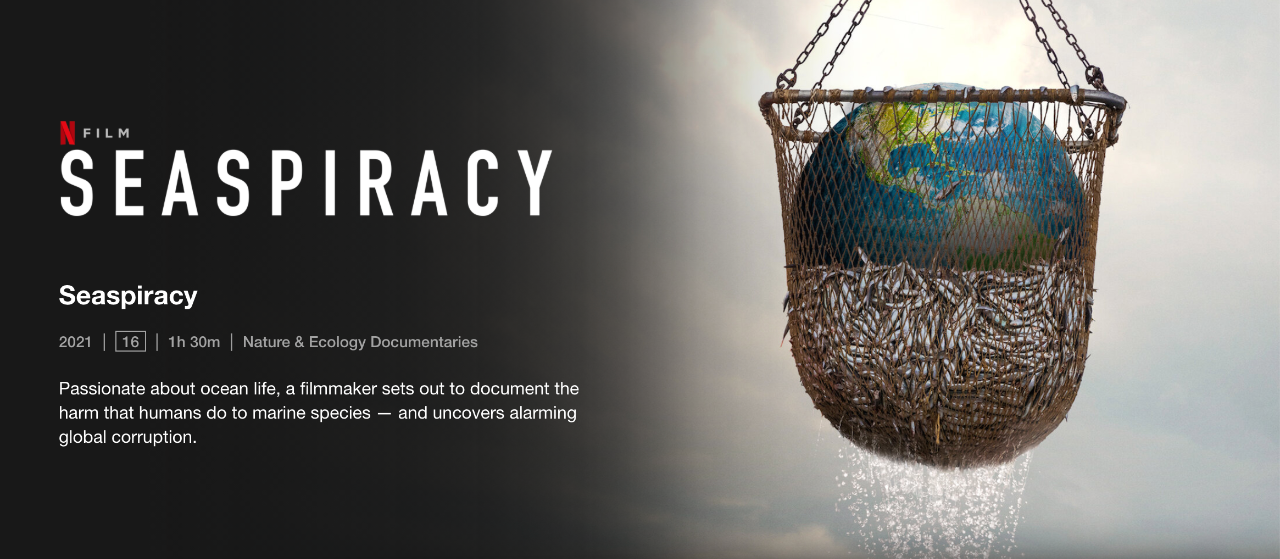

Eating fish has left a bad taste in my mouth. Three tins of supermarket-bought certified dolphin-friendly and sustainably sourced tuna are burning a hole in my cupboard and there’s a guilty-feeling in my previously fish-happy stomach. Why? I’ve just finished Seaspiracy, Netflix’s eye-opening exposé on the damage industrial fishing is doing to our oceans, our natural world, and ultimately, to us.

Given everything the documentary covers – not-so-sustainable certified-sustainable seafood, mega-trawlers clearing 3.9 billion acres of seabed per year, huge swathes of discarded plastic fishing nets floating in the Pacific - whether we should stop eating fish seems like a no-brainer. But in reality, it’s a bit more complicated than that. The UN Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) estimates around 800 million people’s livelihoods are dependent on fisheries for survival and globally, well-managed, sustainable fisheries do exist.

We are undoubtedly having a huge – and in most part detrimental – impact on our oceans. The numbers put forward by Seaspiracy are eye-watering. 2.7 trillion fish are removed from our oceans each year resulting in a massive depletion of fish stocks and marine biodiversity. Mega-trawlers scrape the seabed with nets big enough to hold up to 13 jumbo jets, destroying entire ecosystems at a rate 160 times that at which rainforests are being destroyed worldwide. And given that 93% of all carbon is stored in the oceans, recent research which suggests bottom trawling releases as much carbon as international air travel is hardly surprising. According to the film, at the current rate of fishing our oceans will be virtually empty by 2048. Add to this the claims that sustainable fishing labels – that little blue logo which adorns those ‘dolphin-friendly’ tins of tuna sitting in my cupboard – are completely unenforceable and that, in fact, over 300,000 dolphins, whales and porpoises are killed as ‘bycatch’ alongside fishing activities each year you’ll be forgiven for cutting fish out of your diet forever.

But hold off unpacking your freezer just yet. While Seaspiracy certainly highlights — and rightly so — the most extreme and most damaging aspects of the global fishing industry, what it doesn’t make clear is that not all fishing is equal, that there is a big difference between an industrial dolphin-hungry tuna trawler and two men fishing to feed their family from a canoe. The 2048 fish apocalypse has been widely rejected and there are a large number of economically and ecologically successful, sustainable fisheries around the world. The UN FAO has estimated that, in fact, 66% of fisheries worldwide are sustainable. However, despite this, the issues around the industrialisation of fishing – overfishing, the use of hugely destructive mega-trawlers, plastic net waste and bycatch – are still very much alive.

If, globally, over 800 million people livelihoods are reliant on fisheries for survival, what happens to them if we all simply stop buying fish? For many in the global South this isn’t an option – for some people fish accounts for up to 80% of protein consumed, and small scale and sustainable fisheries are vital for the billions of people living in coastal communities, many of which – highlighted by the film – cannot compete with the heavily subsidised Western commercial fishing operations. For many, there are few economic alternatives, but for some there is hope for innovation and diversification.

Iceland remains one of the only countries in the world to opt out of the International Commercial Whaling Moratorium. And yet, rather than hunting them for meat, ex-whaling ships are now hunting whales for tourism – armed with an intimate knowledge of the water, and cameras instead of harpoons. Tiny Húsavík on Iceland’s north coast is now the country’s whale-watching capital, with over 300,000 tourists per year arriving for the chance to see a giant fluke slap the water, or to snap a humpback breaching. Whales here now have a serious value beyond food.

So, what’s the verdict? It feels unfair that we should be having to make the decision whether to eat fish or not. The onus shouldn’t just be on us as individuals. It is not simply consumer demand that is driving the nets of mega-trawlers across the sea floor, but big fishing companies’ demands for profit. We need to be lobbying government and big business to make the change. It is as much their responsibility as ours. In the meantime, however, I’ve seen enough to be steering clear of the supermarket fish aisle.

Tarring an entire industry with the same brush is an overly simplistic approach – clearly not all fishing is the same - but it is effective. While critics have hit back that the documentary uses out-of-context interviews and is misleading, Seaspiracy makes its point well. As Professor Callum Roberts – a marine conservationist at the University of Exeter who is quoted in the documentary – said in an interview with the Guardian, “My colleagues may rue the statistics, but the basic thrust of it is we are doing a huge amount of damage to the ocean and that’s true. At some point you run out. Whether it’s 2048 or 2079, the question is: ‘Is the trajectory in the wrong direction or the right direction?’”. This film has the potential to be to the most damaging of industrial fishing what Blackfish has been to marine parks. And those tins of tuna in my cupboard are unlikely to be replaced anytime soon.

Want to be part of the solution? Donate to our Save our Oceans United Action. We've bundled the best performing organisations so you can donate to several solutions at once.